With Earth Day having just recently passed, to say nothing of the many natural disasters this week, we are once again reminded of the fragility of both human life and the planet we humans share. We often take our comfortable lives for granted, believing that the earth will be able to support us, as it always has – but the sad truth is that it won’t.

Disasters like the tsunami that claimed the lives of so many in Indonesia and Thailand, the Sendai Earthquake, Hurricane Sandy, and the quake in Nepal remind us that this world is far from a perfect place, even if it’s the only home we have.

And while we’re good at pitching in to help after a disaster, we don’t do a good job of looking out for what’s ahead.

Not when climate change and the destruction of the environment are two of the greatest issues we face in the coming years, issues we are making worse as our economies grow and our countries modernize, our constant demands for energy, water, and more greater with each passing year.

Most of us know this, at least on an intellectual level.

After, the scientific community has been talking about it for close to fifth years, and the rest of us at least twenty, but even knowing what is happening, we’re stuck on one very important issue: how do we fix it?

How do we tackle the greatest challenge our species has ever faced?

The answer isn’t just technology – thinking that it is kind of got us into this mess in the first place.

Nor is it just education, since most of us know what’s wrong with the world in general – its the particulars we have issues with: what’s causing it, what can we do about it, or even if we can.

Partially, its an issue of scale. When you look at a global problem, its hard to think that any one person could make any headway.

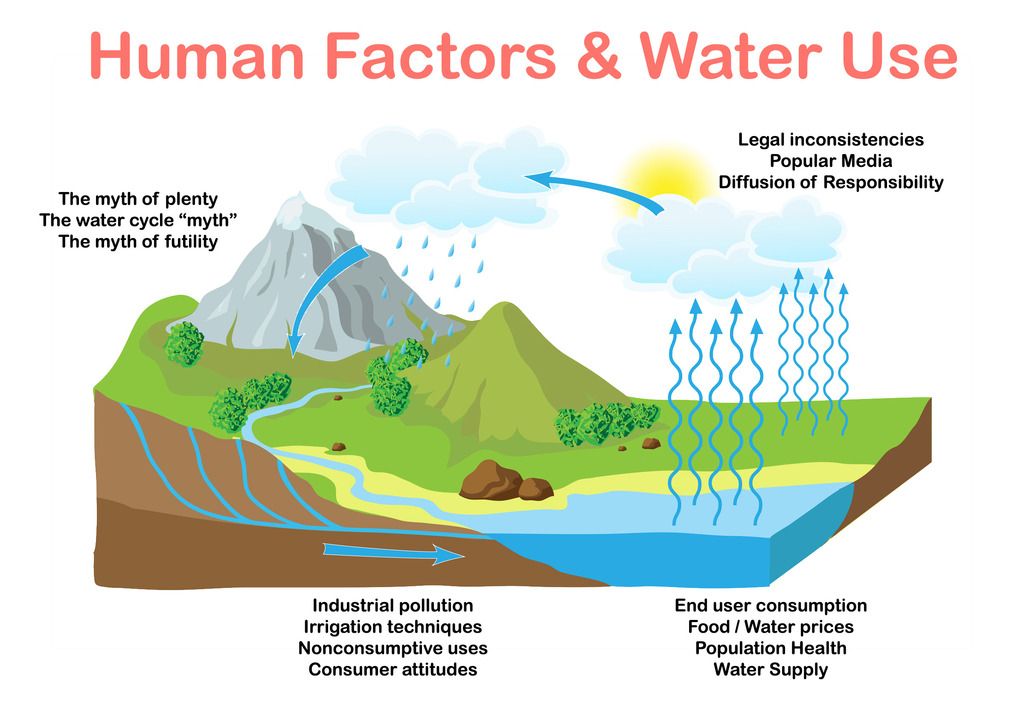

And even when we know how, many of the current systems in place don’t help, with this, as pictured above. There’s very little that makes people choose cleaner, healthier, environmentally-friendly alternatives in the society we live in, so even knowing what the issue is, there’s very little incentive to change.

The issue comes down to one thing: enabling choices.

Because, fancy technology and pie in the sky dreams aside, solving the crisis relies on people making wiser choices financially and environmentally, not just knowing what the problem is.

And where many people think that the answer lies in putting down our devices and looking at the world, at AFK Studios, we think that approach is short-sighted, and just plain wrong.

Because trying to force people to do something they don’t want just doesn’t work, not when they need their devices and connectivity to function in society today. We need to work with what people want, to see how to use what they do to help them learn what they can do.

We at AFK Studios believes that games are part of the answer (and the G20 clearly agreed, since we were invited to the summit as a Global Challenge finalist to speak about how well-crafted games could help with water and water management).

After all, from a designer’s standpoint, games are all about (or should be about) meaningful choices. Behind the graphics, the rich music, and everything else are systems of thought and interaction that lead people towards certain ends and certain goals, provoking thought, challenging mindsets, and encouraging certain choices by making them more rewarding.

And from listening to people talk about choice in games, we can learn quite a bit about human behavior in real life. For instance, in Dragon Age II, there is a moment where one of your party members has just set off a world war, and you have the choice whether or not to execute him. Some believe he was justified, but among those that didn’t, most spared him anyway because he was their party healer and without him, the final set of fights would have been brutal, at best.

That’s the issue in a nutshell.

We may well want to change the world, but as humans, we’re not going to give up our creature comforts.

But at AFK Studios, we think people shouldn’t have to. We think that using guilt and shock to force people to look at a situation is a mechanic that is quite tiresome, and is turning many away from charity and volunteerism. It sends the wrong message, because people don’t like to be uncomfortable – don’t like to be told what to do.

As a studio, we think the power of games can be used to engage people, to lead them to making better choices because an issue matters to them, not just because people say it should matter. We think games can harness the power of imagination and make people want to help.

Pangea is one example of this. A Real-Time-Strategy (RTS) game featuring animals as units, and their ecosystems in the place of the usual civilizations, Pangea blends gameplay, education, and activism into one coherent whole through the power of play and the power of the imagination.

For instance, imagine ordering beavers to create a dam – and then breaking that dam at an opportune moment to wash away a pack of predators trying to cross a river towards your territory.

Imagine commanding an army of sinister looking markhor (war goats) upon the steppes, nimble creatures capable of climbing where a horse never could, holding territory by stamping out an onslaught of venomous snakes.

Imagine wombats charging valiantly against a much bigger foe, their paws pounding the earth as they fight in defense of their burrows.

Imagine duck-billed platypodes (the actual plural of platypus) lurking in a small stream, with hapless predators that seek to cross reduced to helplessness by their debilitating venom.

Imagine all these things and more – a eagle swooping down and carrying off a wargoat perhaps, monkeys setting up wasp nests in trees to delay enemies, and so on. These are all things animals do in real life, but we never hear about them – and we certainly don’t hear about them in games. Most of the time, animals in games are these for us to interact with: to ride, to hunt, to have as a pet. Most of the time, they’re limited to horses, wolves, sheep, pigs, dogs, and the like, with the occasional snake thrown in there for good measure.

Until now, most RTS games have focused on humans and human civilizations (or humans and an assortment of aliens, some more beast-like, some more technologically oriented).

Even Age of Ornithology, pictured above, was only an announcement (an April Fool’s joke at that), not a true game – which is a pity, given that it actually could have been fairly fun. Which is the point – that it is possible to make games that raise awareness of specific issues, but are fun.

Ask yourself this: what don’t see in games? And what opportunities are we missing by not putting them in games?

With amphibians, great reptiles, birds, and others, the answer is obvious.

Fun. Bold new mechanics and things that shake up the conventional formulae. New ways of interacting with the world. New things we can learn. Just as an example, by focusing on animals in their native ecosystems and showcasing just what each of them can do, [em]Pangea[/em] promotes not only an awareness of biodiversity, but also how intriguing these creatures can be – especially the ones we are in danger of losing forever.

Today, most of us are fundamentally disconnected from the world by virtue of where and how we live. That’s why conservation is difficult, as we don’t understand its importance. At best, we focus on how things affect humans, but not some exotic species of wildlife. Why should it matter to us if some species we’ve never heard of goes extinct? Why should we care, when they’re not important to us?

Why should we care, when all we see in the media is how dangerous most of them are, aside from a few conservation poster-children like the giant panda?

That’s why something like Pangea is necessary. Something that delivers the message that animals and their ecosystems are pretty awesome things and are worth protecting. Something that lets you see and command a dizzying array of animals and abilities, so that what others see as danger, you see as virtue and opportunity. Something that lets you see just how dangerous the loss of what people write off as inconsequential may actually be.

In this game, each player takes command of a fledgling ecosystem, based on real-life examples from each major region of the world, choosing how they will adapt to face new challenges and how to spread their territory through barren lands. From humble beginnings – an oasis, the first seeds washing ashore on an island, a few birds coming to new land – they will shepherd their biome along a path that begins with humble scavengers and ends with apex predators that have become legendary the world over.

And each ecosystem has different strengths. A player who chooses an Oceanian ecosystem will have access to a dizzying array of birds, marsupials, and reptiles who excel at colonizing and holding rough terrain without much in the way of resources. A player who chooses a European ecosystem will have more familiar beasts: hares, badgers, foxes, wolves – most of which fare better in either temperate lands – or those already colonized and tamed by other species.

But neither has access to its most powerful creatures at first. To reach those heights, players must gather resources (using their herbivores) and expand their ecosystems to evolve new creatures, choosing what path to take as they develop and specialize in the backdrop of a persistent living world that they will help create.

Should they wish, they can build up a hidden valley for themselves, self-sufficient so long as they manage it well. Should they wish, they can explore and leave scattered outposts – oases – in the barrens for others to use. And of course, those who wish can wage wars of conquest and expansion, seeing how ecosystems clash and sometimes worth together, both against each other, and against a strange Wilderness from the distant past.

Through this, we seek to let people learn how ecosystems work through play, discovering what works – what does not – and telling their own stories of exploration, growth, and survival, building awareness of why these things matter, and getting people to feel a sense of investment.

Because to make change, you need to feel invested in that change.

New Zealand’s Forest and Bird Society and Design Global Change agree, as they are two of our partners in developing Pangea. We’re reaching out to other charities and non-profits around the world as well, because we think if you want to change the world, you need to think about systems and design – because these systems are how we interact with the world. We think that the power of play is critical in engaging people where traditional means fail, allowing them to feel a sense of wonder and discovery.

We think through games, we can change the world. Join us in making that a reality.